In late May 1965, Coca-Cola contacted Charles Schulz, the creator of the Peanuts comic strip, and commissioned him to create an animated Christmas special that the soft drink company would sponsor. With just six months to produce the television program, the cartoonist immediately called a meeting with his producer, Lee Mendelson, and with the show’s director, Bill Melendez.

The three men met over Memorial Day weekend at Schulz’s home in Sebastopol, California, and together they sketched out the key elements of what would become the most popular animated Christmas special of all time – “A Charlie Brown Christmas.”

Lee Mendelson suggested a Christmas tree as a plot element. Schulz embraced the idea, saying, “We need a Charlie Brown-like tree!” When the producer next suggested inserting a “laugh track” (the recorded sound of an audience laughing), Schulz was offended.

“I quit,” objected the artist, and he stood up and left the room. Melendez broke the tension by joking, “Well, I guess we won’t have a laugh track.” Schulz reentered the room and the meeting resumed.

I TRULY UNDERSTOOD MEMORIAL DAY WHEN I BECAME PART OF THIS GOLD STAR FAMILY

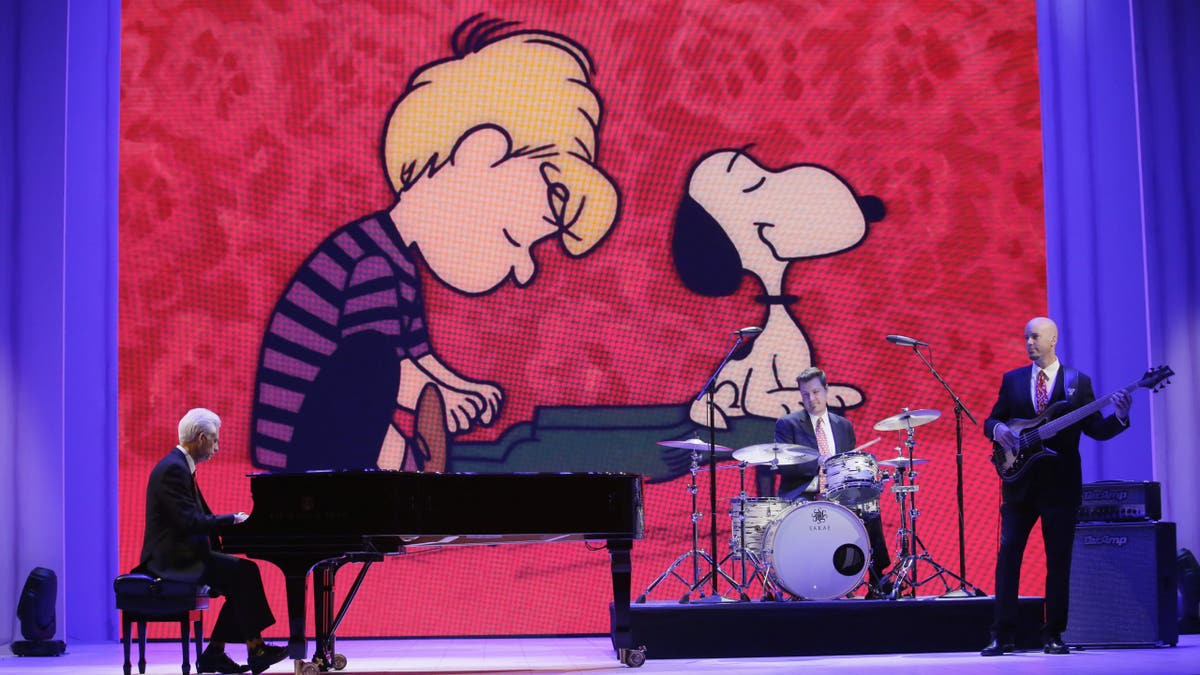

The program’s music was also a topic of discussion. The men agreed to engage jazz composer Vince Guaraldi, who two years earlier had produced the soundtrack for a documentary about Schulz that had failed to find a buyer.

Schulz also wanted to insert a scene where Schroeder, his piano playing Peanuts character, could play a Beethoven tune. The cartoonist also insisted that the voices of the characters be those of actual children, not professional adult voice talent.

The most contentious issue arose when Schulz proposed having Linus recite biblical verses from the Book of Luke. “We can’t do this; it’s too religious,” said Melendez. “It just doesn’t belong in a cartoon.” Lee Mendelson voiced the same concerns.

The Bible had never been animated before, not by Warner Bros., not by Disney, and not by Hanna-Barbera. Inserting an overtly religious scene would potentially expose the program to attacks from both Christians and non-believers.

AMERICA’S WAR HEROES BURIED OVERSEAS REMAIN DEFENDERS OF LIBERTY: THEY ‘CONTINUE TO SERVE’

Churchgoers might object that animating the Bible and having its sacred verses spoken by cartoon characters was sacrilegious. Those less religious might be turned off by preachy moralizing. Schulz was undeterred by his colleagues’ objections asking, “If we don’t do it, who will?”

At one point, the three men took time to relax in Schulz’s swimming pool. Schulz, a combat veteran of World War II, lamented to Mendelson that Memorial Day’s true meaning had been lost and the holiday was now merely a kickoff to the summer season and an occasion to barbecue.

Now the cartoonist feared the same thing was happening to Christmas. The real meaning of the holiday was being lost and replaced with a secular celebration of Santa Claus.

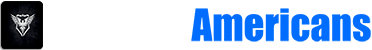

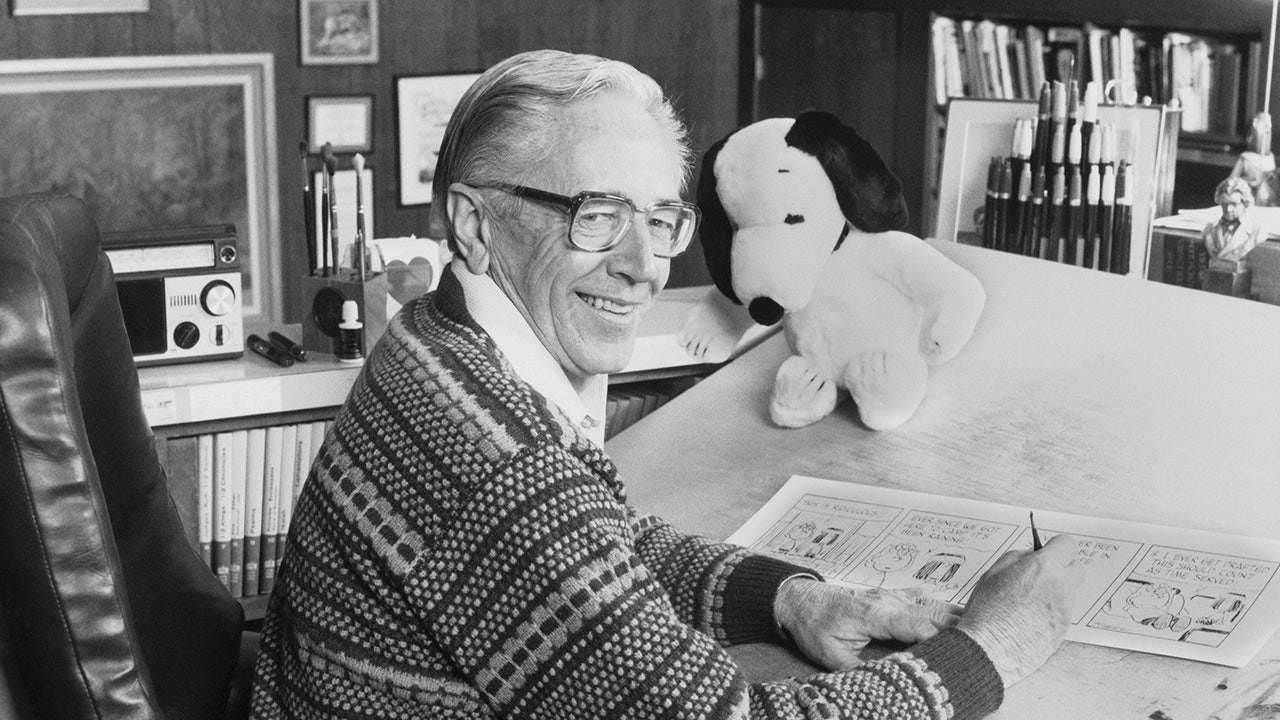

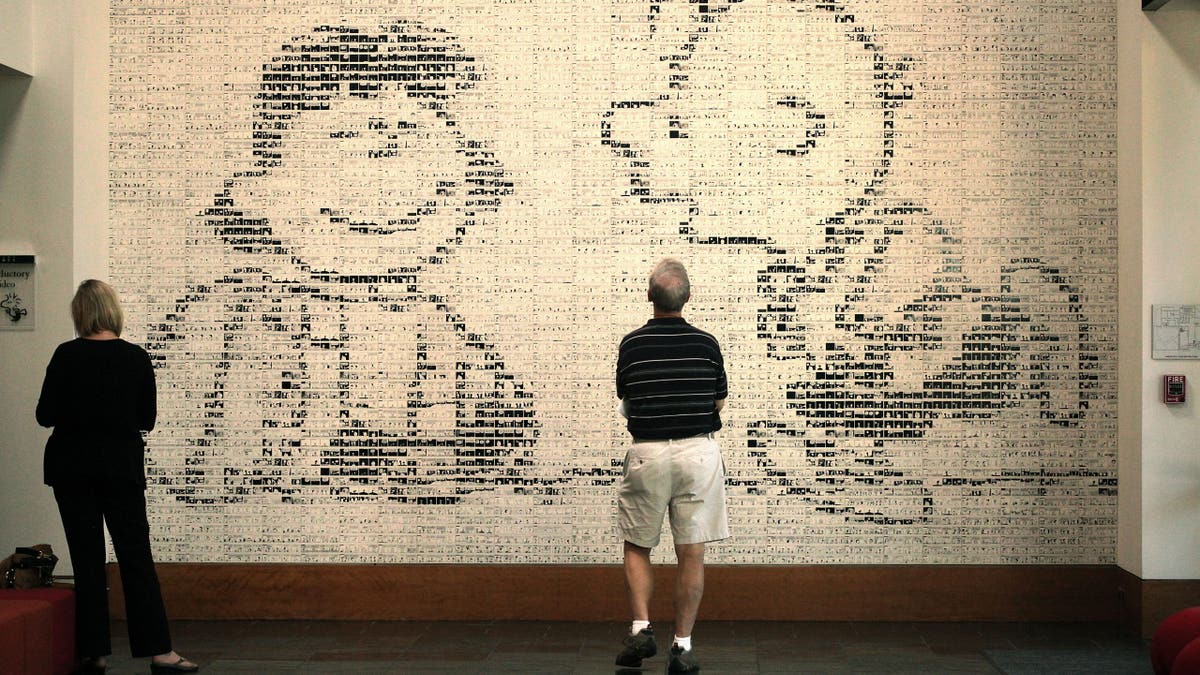

In 1965, Charles Schulz was well on his way to becoming the most successful comic strip artist of all time. His Peanuts comic strip reached 60 million people and was published in over 700 newspapers in the United States and Canada and an additional 71 internationally.

3 THINGS I WANT MY CHILDREN TO KNOW THIS MEMORIAL DAY

His recent book “Happiness Is a Warm Puppy“ had become an instant New York Times bestseller. Licensing opportunities were piling up. He had just been awarded the National Cartoonists Society Award for a second time.

However, when a visiting reporter asked Schulz what accomplishment he was proudest of, the cartoonist did not mention Peanuts. He instead pointed to a framed three-inch wide rectangular bar of silver and blue enamel displayed on his office wall and said, “My Combat Infantryman Badge.”

In 1943, at the age of 19, Schulz had reported to Camp Campbell, Kentucky, having just lost his mother to cancer. The combined impact of bereavement, loneliness and the shock of basic training traumatized the skinny, innocent teenager from St. Paul, Minnesota.

But the same insecure kid who had recently flunked every high school course in a semester displayed a competence and intellect during boot camp that saw him promoted to buck sergeant and squad leader when his unit shipped out for duty in World War II a year later.

MEMORIAL DAY IS A REMINDER FREEDOM ‘MUST BE FOUGHT FOR AND DEFENDED CONSTANTLY’

Schulz manned a .50-caliber machine gun in a halftrack in the U.S. Army’s 20th Armored Division as it rolled through France, Belgium, the Netherlands and finally into Germany. In addition to experiencing the horrors of combat, Schulz’s unit also took part in the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp.

His wartime experiences left an indelible psychic wound on Schulz, but it also forged Schulz into a committed Christian who was grateful to God for having survived World War II.

In December 1965, when Schulz’s Christmas special was screened for two CBS vice presidents only a week before its scheduled broadcast, the network executives were disappointed by its rough animation, dismayed by its jazz music score, and disturbed at its undisguised religiosity.

The network ultimately resigned itself to broadcasting the program, convinced that the show would be a ratings bomb. A CBS executive bluntly informed Mendelson that the network would never buy another special from him or Schulz.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE FOX NEWS OPINION

“A Charlie Brown Christmas” aired on Thursday night, Dec. 9, 1965. Almost half of the television viewers in America tuned in, and the reception of the audience was overwhelmingly positive.

The show’s climactic religious scene that Schulz had insisted on had resonated with viewers and seemed to transform the whole program from an amateurish flop into an enduring triumph. (The recitation from Scripture was performed by the blanket-clutching character Linus and concluded with a line that had to have special meaning for the combat veteran: “Peace on earth, goodwill toward men.”)

“A Charlie Brown Christmas” would be recognized with an Emmy and a Peabody award and become America’s most popular animated Christmas special.

Schulz succumbed to colon cancer in 2000 at the age of 77, passing away the same day that the last comic strip he had drawn was published. His simple grave marker makes no reference that he was the creator of the multi-billion entertainment property Peanuts, but it does reference what the cartoonist considered his life’s proudest role. Following the name “Charles M. Schulz” and above his dates of birth and death, the bronze grave marker notes the following, in capitalized raised lettering:

SGT US ARMY

WORLD WAR II

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM MICHAEL KEANE

Read the full article here