Depending on the load, a .30-06 has a power factor of about 400, but 12-gauge slugs can reach the 700s with ease.

If you really want to put the hurt on something, like a big critter, a 12-gauge slug does that. And here I will be speaking only of the 12-gauge variety, because while the 20 can come close, the rest … meh. The 16-gauge is so rare that it might not even exist, and 28 and .410 slugs are pointless.

First, what’s a slug?

Simply put: a single projectile, not a payload of shot or buckshot. And the shotgun slug goes back a long way. In fact, until the advent of the Minie ball, you could say that everyone fought wars with shotguns and slugs.

Really.

The near-ubiquitous Brown Bess—the British Army standard from its finalization in 1716 or so until it was replaced by a rifled musket in 1867—was what ruled the world. The Land Pattern musket fired a round ball of about 0.700 inch in diameter: The black powder charge pushed it to over 1,000 fps, so it was essentially a “low-recoil” 12-gauge shotgun.

Well, round balls aren’t what we use today, but shotgun slugs are still with us. What are the slugs’ designs, you ask? Well, it depends. It depends on whether you’re using a smoothbore or a rifled-bore shotgun. Yes, it’s possible to have a fully rifled bore and still be a shotgun. That’s one of those regulatory determinations that had to be made, as the technology advanced and shooters demanded more.

We’ll go into that in a bit.

The basic slug is called the “Foster” slug. Think of a lead shot glass with a round base.

Load the slug/shot glass base-down and fire it rounded-end forward. No, it doesn’t act like a Minie ball. The open edges, or the skirt, can’t expand to grip the (non-existent) rifling, because shotgun slugs of the Foster design are loaded with wads underneath them, ahead of the powder charge. There’s often an assembly or stack of wads, with an over-powder card, then a cushioning and a slug base card. The slug and the wad assembly are pushed down the bore, and the slug continues while the wads drop off.

But the wads can be problematic. If you’re hunting, no big deal. The cardboard, pasteboard or other wadding will simply decompose in the woods. And the wads don’t go far enough to be a problem. But, in defense they might. Inside of, say, 15 yards, wads can hit hard enough to cause an injury … especially now that they’re all plastic, not card and fiber. They can stray wide of your line of fire, so if you’re using Foster slugs for defense, you have that to keep in mind.

How do we solve that problem?

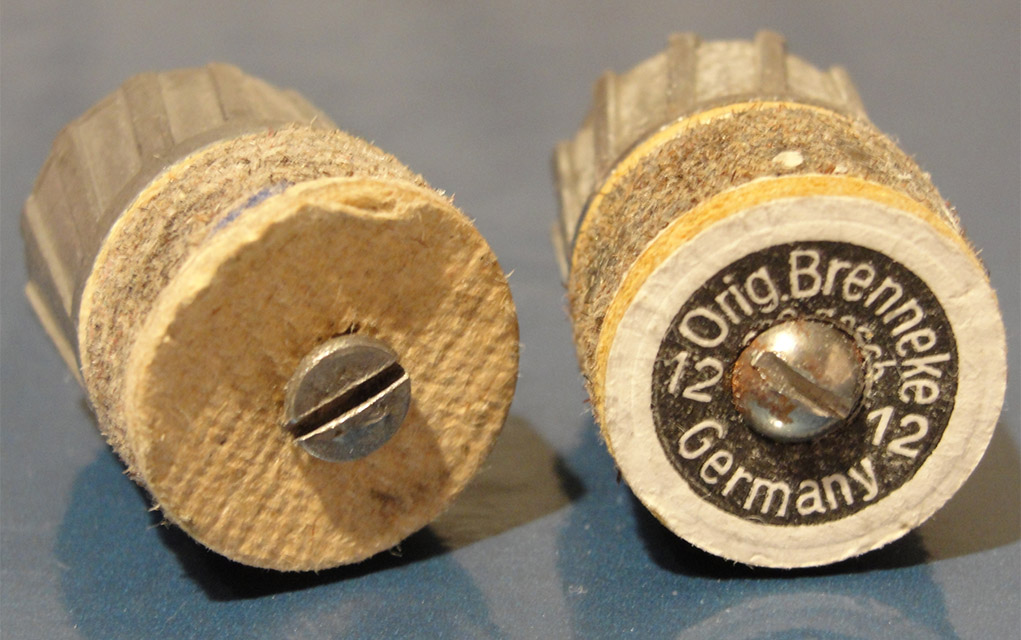

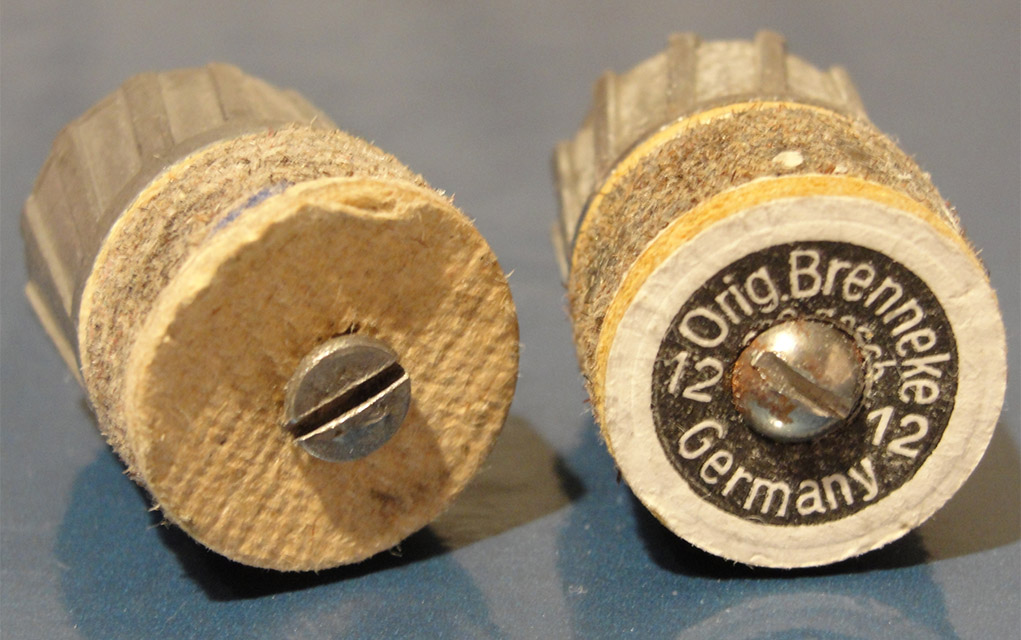

Brenneke had a simple solution. Instead of the lead cup, the idea is to make a lead cylinder. Then, use a screw to attach the wadding column to the base of the cylinder. Fire the whole assembly, and voila, no wadding straying off your line of fire.

Typically, the Foster slug tends to be made of a soft lead alloy, so it can squeeze down if you happen to fire it through a barrel with some choke constriction or a choke tube installed. The Brennekes have the lead cylinder on the small size of bore diameter and use the wadding to keep it centered in the bore. So, it can pass through some chokes without damage.

But, after all, rifling was invented for a reason. Modern shotgun slugs are more accurate than the smoothbore muskets of yore for a couple of reasons.

One, they’re machined to tighter tolerances than a Land Pattern musket. Two, the modern slug is a lot closer to bore diameter, so there’s less “wandering” as it goes down the bore. The British soldier who was furiously loading his musket might be dropping a 0.680-inch ball down a .700 bore. The idea was speed of loading and volume of fire.

The dimensions don’t vary nearly as much today. And then there’s physics.

The best description of the stability methodology of a shotgun slug (so far) is “a rock in a sock.” The Foster slug has its center of mass forward of its center of shape, and that keeps it more-or-less traveling in a straight line. The Brenneke has the attached wadding column to do the same thing, making the center of mass forward of the center of shape. And the air flow over the wadding adds to that. The ribs on the slug do nothing for accuracy or create spin. They are to reduce stress on your choke, if you forget.

When the dimensions all work out properly, the accuracy can be quite startling. I built a shotgun slug gun for use at the Second Chance combat shoot (now The Pin Shoot) way back when the elder Bush was president. That gun grouped Remington 7/8-ounce slugs into one ragged hole at 50 yards, all day long. (Of course, Remington stopped making that load.) But you can certainly get minute-of-whitetail out to 100 yards once you find the combo your shotgun likes.

The Sabot

Another approach, one not so common these days, is an aerodynamic sabot slug. Sabot, from the French word “sabot” for a wooden shoe (and the root of “sabotage”), throwing a wooden shoe into the gears of a machine as the origin. The sabot is a pair of molded plastic sections that fit around the slug, which rides in the center. The sabot was made sort of wasp-shaped and smaller than the 12-gauge bore. So, a .500-inch slug with plastic sleeves. The sleeves, or sabot, would fall away once it left the muzzle, and the aerodynamic slug would continue on. This has the same wadding problem as the Foster slug.

The modern iteration of that is to use a jacketed 0.50-inch bullet, with a spire point inside of a sabot in a rifled-bore shotgun. The accuracy of this arrangement can rival that of rifles. Why do this? Because some locations still require a shotgun, not a rifle, for hunting. And because the DNR would find keeping rifled-bore shotguns out of the hunting fields a herculean task, they approved them.

The Lyman

Now, in all these there’s one more slug to consider: the Lyman. I view it as the “12-gauge airgun pellet” slug … because that’s what it looks like. It’s cast (you must do the casting, no one I know of makes them, either for loading or as loaded ammunition) with a special mold that creates a hollow-base pellet, just like the airgun one but 12-gauge. It then gets loaded into a regular shotgun and into a shotgun hull. This leads me to the shotshell and its crimp.

The Shotshell

A regular shotshell uses a folded crimp of six or eight petals, and it seals the shot or buckshot in the shell. In the old days, when shells were paper, it was an over-shot card, and the load data (shot size, weight, charge) was printed on the card.

Slugs were loaded with a roll crimp. This does two things. One, it makes the shot and slug loads instantly identifiable, even by touch. Two, the roll crimp resists unfolding more than a folded crimp, and this permits powder charges that create more velocity with slugs than birdshot. Where a fast load (in lead terms, steel shot is a lot zippier) of shot might be 1,350 fps, a slug can be made to produce 1,600 fps. And recoil to go with it.

The Lyman slug uses a regular folded crimp, with regular, if specific wads. So, in addition to needing to follow exactly the specific load data for the Lyman slug, you need to load it in hulls that you do not use for any other purpose. So, just as an example: If you use Winchester AA red hulls for your skeet and trap shooting, you cannot use them for the Lyman slug. Otherwise, someday you’ll mix them up, go to shoot a round of skeet and be hurling 12-gauge slugs off into the distance. No, load those slugs in something not red at the very least.

The Recoil

And that brings me to the last part: recoil. As in, shotgun slugs have it in spades.

You might’ve noticed that I used quotation marks when describing some shotgun slugs as low recoil. Well, let’s take a common new one, the Federal Tru Ball, which is 438 grains of slug at 1,350 fps producing a power factor (PF) of 591. A .30-06 can tap in at “only” a 405-410 PF. Winchester matches that with their sabot and a 1-ounce slug at 1,350 but then ups the ante with a 1-ounce slug at 1,600 fps. That’s a 700 PF. Ouch. Dialing the recoil back to a “low-recoil” load, of 1 ounce at a mere 1,150 or 1,200 fps, is still a 504 or 526 PF.

So, keep in mind that, whatever thumping you’re doing on the other end, you’re going to be receiving a thumping of your own on this end. However, if you want something light and handy, fast to use, and that hits hard, a shotgun (pump or auto) loaded with slugs can be a winner. There’s a reason those who travel in bear country look favorably on a shotgun with slugs.

I don’t do much of that traveling, and when I do, someone else is hauling the ordnance. But I do use shotgun slugs. In my case, it’s with the Lyman slugs, loaded to tolerable velocities, in The Pin Shoot. There, the task is to knock over hinged steel plates and complete the array faster than anyone else does.

Now, this is a specialized competition and perhaps not for everyone. But it does serve another purpose. If you were planning on going, say, fly-fishing in bear country and wanted to take a shotgun for defense, practicing with factory “ohmyrecoil” slugs would be both expensive and painful. However, if you pored over the Lyman shotgun loading manual and found a load for your Lyman slug that wasn’t painful to shoot, you could do a lot of practice without a lot of recoil.

And that’s always good.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the May 2025 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

More On Shotguns:

Read the full article here