Technological revolutions inevitably tend to create periods of “before” and “after.” Some of us can remember life before “the world wide web” or desktop computers. For just about all of us, however, it’s hard to imagine getting through a week of work without having to answer a litany of emails. Once the future arrives, it tends to stay. It may even stick around for so long that we begin to take it for granted.

Though the world of handguns has been defined by constant refinement and innovation, we owe a particular debt to the work of one designer: John Moses Browning. I would argue there’s a world that existed before him, and the world we continue to live in thanks purely to his influence.

Pistols Before John Moses Browning

If you look at most of the early autoloading handguns circa 1900, you’re bound to emerge with one overriding conclusion: these things are really, really weird. A litany of countries and firearms designers were trying to crack the code of using the energy of a fired round to eject its metallic casing and load the next cartridge, but the designs show they were throwing anything at the wall to see what would stick.

There are a variety of oddities to be found at this time. Most rely on some kind of reciprocating bolt that strips rounds out of a forward-mounted internal magazine. Picture the famous C96 Broomhandle Mauser, and you’ll have a good idea of the archetype. The Schwarzlose 1908 even had a “blow forward” action, where the slide would move forwards under recoil, and spring tension would push it backwards to chamber the next round.

Although they worked (usually), these mechanisms were remarkably ungainly, such as Hugo Borchardt’s C93 pistol and its bulbous rear protrusion of the action. The C93 holds the distinction of being the world’s first “locked breech” pistol, instead of the vastly more simple “blowback” operated firearms. It was also the first pistol to utilize a detachable magazine. However, and hilariously, Borchardt claimed he had perfectly solved the autoloading puzzle and handguns could not be improved any further. Georg Luger and his famous P.08 would almost immediately prove Borchardt wrong.

Lightning Strikes Twice

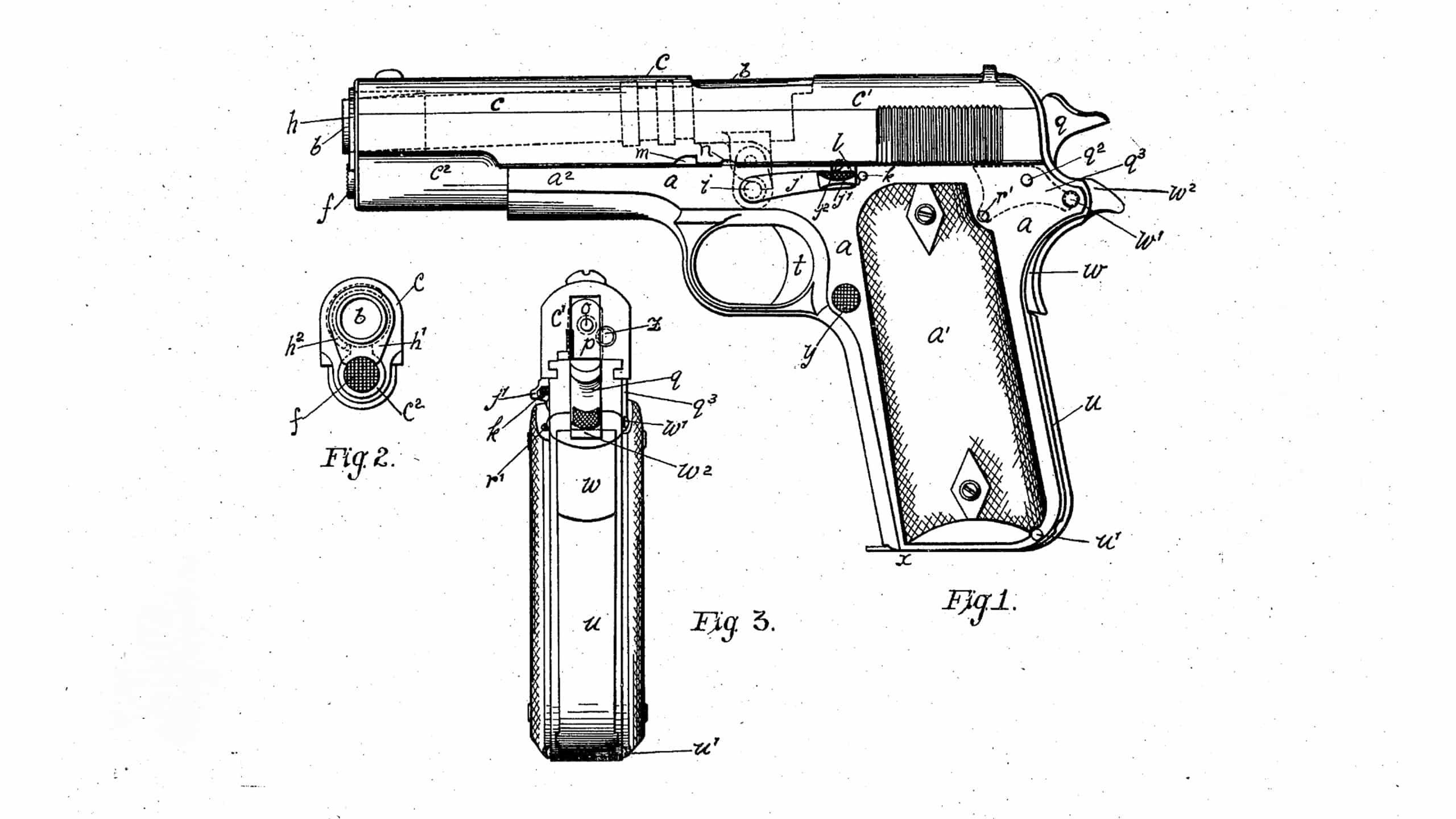

Though John Moses Browning certainly invented a number of other quality firearms, his autoloading handguns — and particularly the model of 1911 — represented a tremendous leap forward in firearms product development. While the gun is more than a century and a decade old, Browning’s design pioneered aspects of the modern handgun that remain with us even today — and are in no danger of disappearing anytime soon.

Firstly, Browning popularized designs with a reciprocating slide that enveloped the barrel. This rectangular, “parallel ruler” configuration could be easily grasped and manipulated to charge the pistol, unlike the various wings, bolt ears, toggles or cocking pieces of then-contemporary designs. At the same time, these slides were relatively simple to machine with respect to the model’s competitors, allowing for lower production costs and higher manufacturing volume — details that would be quite salient come wartime.

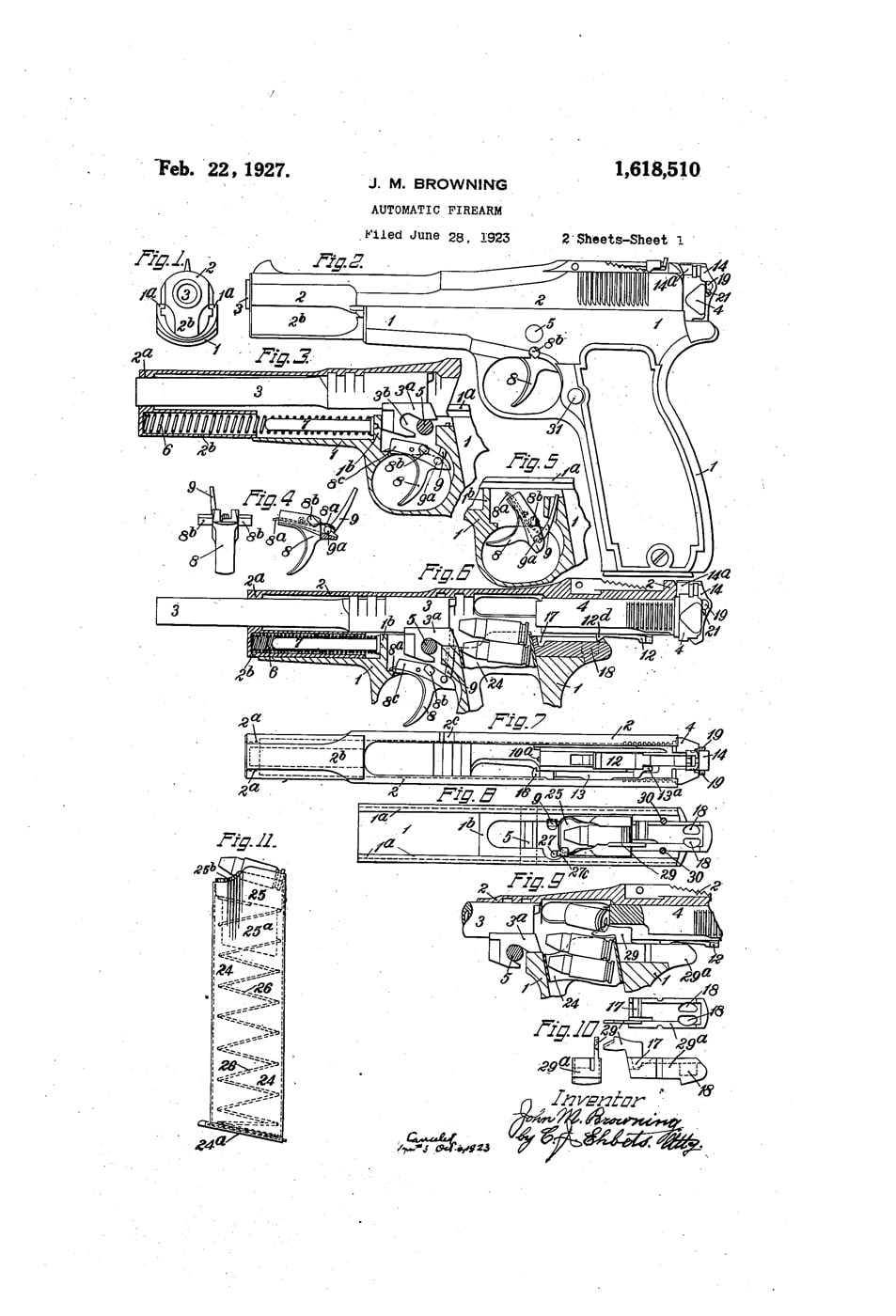

What’s even nuttier is that for a while, Browning’s “swinging barrel link” mechanism was under patent — so the inventor came up with yet another locking system. When designing the iconic Hi-Power, John Browning once again broke the mold with the tilting barrel locking system: every time you encounter a pistol in which the barrel seems to cam upward when the slide is retracted, guess what: you’re seeing this locking mechanism in action.

Today, there seem to be more centerfire handguns relying on this method of operation than those which lack it. At Springfield Armory, for example, you’ll find tilting barrel locking systems on Hellcats, SA-35 pistols and the Echelon models.

Perhaps the best compliment that can be paid to Browning is that his designs flat-out worked. In the original military trials for the 1911, Browning’s sample gun digested a staggering 6,000 rounds without failure over a course of two days. When the gun became too hot to handle, the test 1911 was reportedly dunked in a bucket of water and shooting resumed unimpeded. Additionally, just about everyone has used the tilting barrel recoil operation system on their handguns because — as of yet — no one has invented a more simple and elegant mechanism.

A Modern Era of Ergonomics

Browning isn’t just considered a genius because of his mechanical know-how, but also due to his understanding of ergonomics. Though the “rakish” dimensions of the Luger P.08 curry favor among contingents of modern shooters, the “Browning” grip angle of approximately 18 degrees seems to be more or less replicated across most other handguns — and is still seen today in many modern handguns.

Interestingly, Browning began modifying the 1911 design in 1924 at the request of the U.S. Military, who wanted the pistol to be friendlier for smaller-handed shooters. Those changes led to what is officially known as the 1911A1 in 1926. Beyond some smaller revisions such as the lengthened grip safety and frame relief cuts behind the trigger, the biggest change was the addition of an arched mainspring housing, which was intended to address the criticism that the 1911 “pointed low.”

But here’s the kicker: it would seem that time has validated Browning’s original dimensions: even within Springfield Armory’s own catalog of 1911 pistols — and those of most of its competitors — the flat mainspring housing once again appears to be the choice that works for a majority of shooters. At Springfield Armory, only the company’s Mil-Spec line of 1911 pistols has retained the arched mainspring for reasons of historical accuracy.

Shape aside, Browning also standardized the location of the “American-style” magazine release. Additionally, if a pistol incorporates a frame-mounted safety, you’ll almost always find it in the same location it would sit on the 1911 or Hi-Power. Anywhere else simply feels “weird” or “counterintuitive” to no small number of shooters.

The John Browning Legacy Today

I’d be remiss not to mention that if we talked about John Browning in any larger context, we’d be here all day. The man held 128 separate patents, all related to small arms development. It’s also no exaggeration to say that America’s historical ability to fight the forces of fascism, and the international order that exists today, is at least partially John Browning’s doing.

But let’s get back to handguns, and specifically, Browning’s most famous patent. For as much love as the 1911 (deservedly) gets, the plain truth is that it doesn’t work for absolutely everybody under the sun — the number of high-quality pistols made by Springfield Armory is testament to the diverse needs and preferences of everyone, from card-carrying CCW devotees to run-and-gun competition shooters. As one gun store owner I know says, “There’s no perfect gun for everyone. If there were, we’d just carry that and simplify our inventory!”

That said, if there’s a line in the sand that separates the modern era of pistol design from what came before, it was drawn by John Moses Browning. Most all of what feels, looks, or operates in familiar way from handgun to handgun is due almost entirely to his mechanical insight, technical skill, and overall prescience.

If you own a 1911, you probably already knew a little about Browning’s legacy. You might be surprised, however, to find signs of that same DNA in just about every other handgun in your collection — and that’s quite a legacy.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Read the full article here