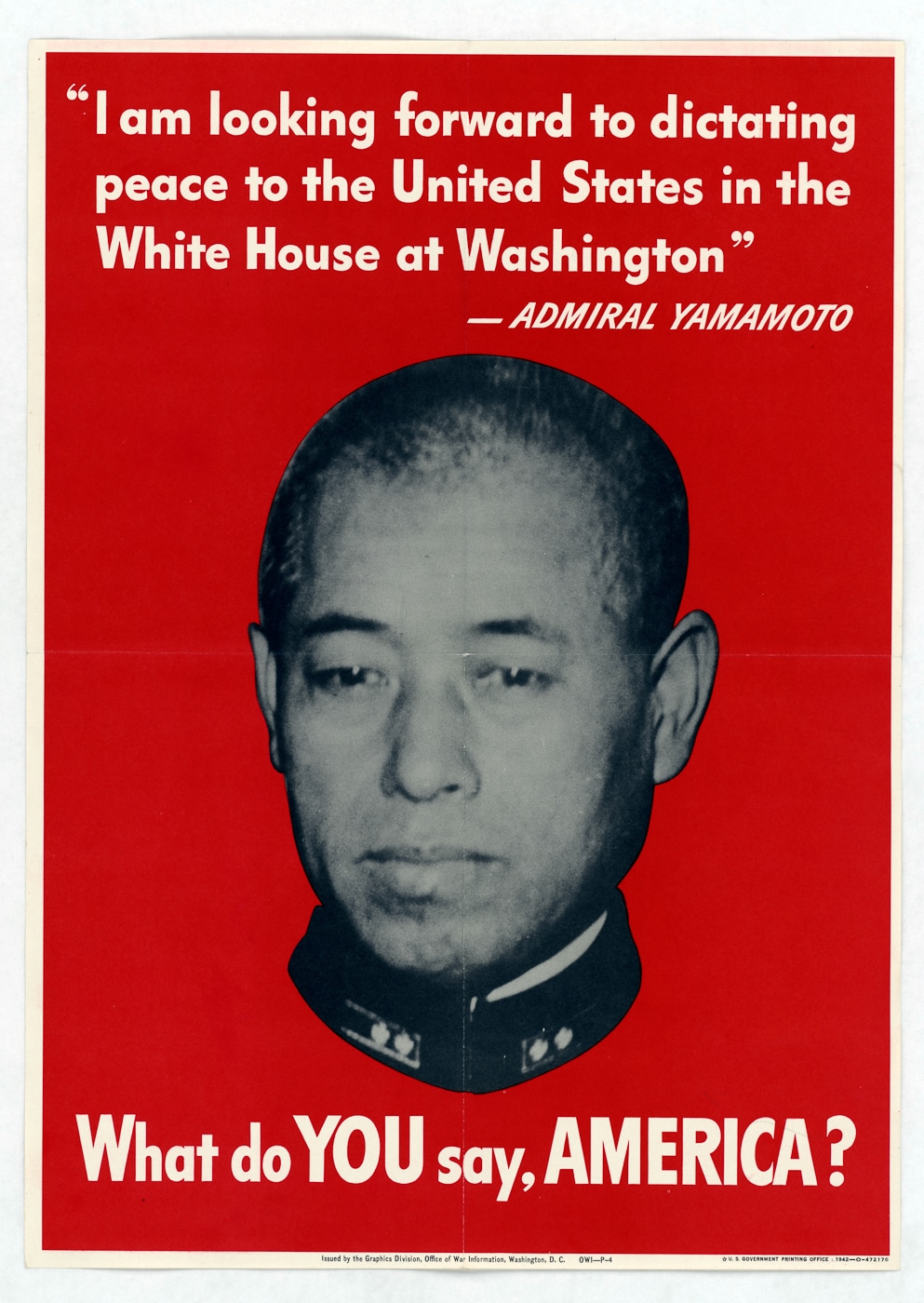

In the early days of the United States’ involvement in World War II, stateside motivational posters proclaimed, “Remember Pearl Harbor”, and “Avenge December 7th”. And while the “date which will live in infamy” focused America’s rage on Imperial Japan, U.S. military planners in the Pacific Theater of Operations (PTO) dreamed of vengeance against the specific planner of the Pearl Harbor attack: Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto.

Yamamoto, the commander-in-chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet, had originally been opposed to war with America, and had made his feelings known privately and even publicly. He warned that he believed Japan could not defeat the United States, as Japanese production could never match up against American industrial might. Even so, political pressure and his sense of duty led him to plan the daring first strike against America’s prime naval base in the Pacific.

By April 1943, Yamamoto’s prediction was proving correct. Japan was locked in a deepening war of attrition with America, and the situation was turning against the Rising Sun. U.S. forces were advancing in the Solomon Islands, more and more Allied equipment was arriving every day, and the United States Army Air Forces (U.S.A.A.F.) and United States Navy were beginning to achieve air superiority in some areas. The Japanese Mitsubishi A6M “Zero” fighter, while still dangerous, was no longer dominant. The tide was clearly turning.

The Breakthrough

After the efforts of U.S. Navy code-breakers paved the way for the “Miracle at Midway” in early June 1942, the signals monitoring and cryptographic intelligence unit kept at their detective work. On April 14, 1943, the U.S. naval intelligence operation, codenamed “Magic”, picked up an important Japanese naval transmission.

Once deciphered by Tech Sergeant Harold Fudenna, the message yielded the precise itinerary of Admiral Yamamoto’s upcoming inspection tour of bases in the Solomon Islands.

On April 18th, the Admiral and key members of his staff would fly from the massive Japanese naval base at Rabaul (at 06:00 Tokyo time) and arrive at Balalae Airfield near Bougainville (at 08:00 Tokyo time). Yamamoto and his entourage would travel in a pair of Mitsubishi G4M bombers while escorted by six Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters.

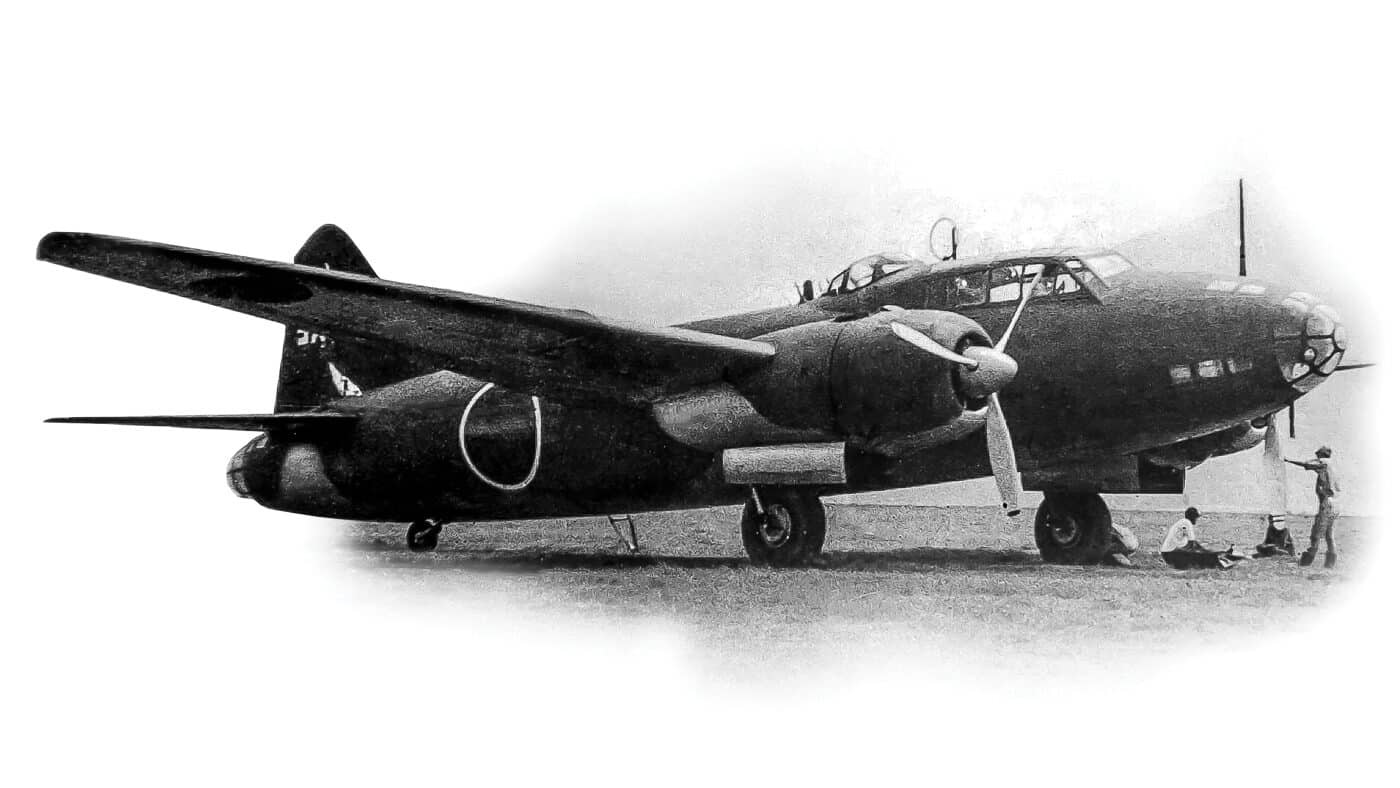

Known to the Allies under the code name “Betty”, the G4M that would be carrying Admiral Yamamoto was not a transport aircraft but rather a land-based medium bomber of the Imperial Japanese Naval Air Service.

The Mitsubishi G4M (Type 1) attack bomber had been in service for two years at the time of the Yamamoto mission and was much prized for its long range — 1,500 miles when carrying a bomb load, and up to 2,700 miles on a ferry mission. But the great range came at a price, and throughout its career the G4M was dogged by its light construction that allowed it to be easily damaged and ignited by gunfire.

Early models lacked self-sealing fuel tanks, and Allied pilots called the Betty the “Type 1 Lighter” or “The Flying Zippo”. There was little or no armor protection for the crew, the fuel tanks or the engines.

Even so, the G4M squadrons had their share of success in the first year of the war, including the participation in the destruction of the battleship HMS Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser HMS Repulse in December 1941, along with the heavy cruiser USS Chicago in January 1943.

Seizing the Moment

At first, American intelligence officers had a hard time believing that the Japanese would be so cavalier as to transmit such a message, even if it was encoded. But additional code-breakers stationed in Alaska and Hawaii also intercepted that message, deciphering it to reveal the same details.

The significance of this intelligence windfall would have been hard to overstate. U.S. armed forces had ample motivation to remove one of Japanese most important chess pieces from the board, and Admiral Nimitz made the call. He judged that the opportunity to terminate Yamamoto and seriously damage the Japanese navy, as well as Japan’s overall morale, was worth the risk of tipping off the enemy that their codes had been broken.

As a code name, “Operation Vengeance” seemed fitting for the mission. Vengeance was clearly on everyone’s mind among America’s military and political leaders. The pain of Pearl Harbor was still fresh, and Admiral Nimitz received permission to proceed from Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox.

Once cleared on the mission, Admiral Nimitz reached out to Vice Admiral William “Bull” Halsey, commander of the South Pacific Area. It was soon determined that there was only one American interceptor that was truly capable of performing this mission, and it was relatively new to the Pacific theater. That plane was the Lockheed P-38 Lightning.

Halsey immediately called upon the U.S.A.A.F. 339th Fighter Squadron based at Henderson Field, Guadalcanal, to handle the interception. Detailed plans for the mission were calculated and mapped out immediately. Vengeance was soon to come, and the Lightning would play an integral part in the mission.

The Right Tool

The P-38 became operational with the 5th Air Force in early March 1943. In that same month, the U.S.A.A.F. prepared a report titled “Tactical Suitability of the P-38F Airplane”, which contained the following information that would be of critical importance during the mission to intercept Yamamoto.

“The visibility over the nose is satisfactory for deflection shooting, but the armor plate window and gunsight obstruct the forward vision for search. To the sides, the view downward is limited by the position of wings and engines, and searching below will have to be accomplished by banking the airplane from side to side. The search view on both sides is greatly obstructed by metal strips where the canopy joins the window. The view to the rear is limited by the boom and rudders, and rear armor plate.”

One of the men who would play a prominent role in the mission, Captain Thomas Lanphier, was interviewed after the mission for a confidential article in a Bureau of Aeronautics publication. The following excerpts provide some insight into how the P-38s were used in their early deployment, and what the combat pilots thought of them:

“P-38s are rugged, they take a lot of punishment. Apparently, they’re vulnerable only in the engine. The pilot is pretty well protected. The Japs thought the P-38s were the best planes they were running into.

“The firepower, four .50-cal. Machine guns and a 20mm cannon, is quite satisfactory. The cannon uses all explosive ammo. The four .50s flying right straight up made a splendid concentration of firepower.

“When … (new pilots) … have flown the planes and learned how stable they are, how well the pilot is protected, what a lot of damage can be dealt out with them — in other words, once they get on a flight — they’re okay. It doesn’t take very long for the ordinary American kid to catch on.”

Regarding Japanese fighter tactics, he had the following to say:

“The Japanese continue to fly as they always have, react the same way to an attack, and do the same fundamental things. I’ve never run into one who, when attacked from behind, would cut his throttle. Their planes, I should think, would stop abruptly if they’d cut the throttle and we’d overshoot them. Some of them are smart enough to pull off to the side, but that is usually taken care of by our wingman. Generally speaking, they still pull right up in the air, or roll upside down and go straight down, which puts them out of the fight. The Japanese pilots coming over are not so smart as they used to be; they are probably running into the dregs now.”

On P-38 tactics against Japanese fighters, he stated the following:

“I had a four-plane section which had flown together for about a year, which is unusual for the Army. Each of us felt very responsible for the others; I was responsible for my wingman, and he was for me. We never had occasion to use any evasive maneuvers; we were never surprised from behind. We had planned that if we were completely surprised and had to get out in a hurry, we would pull off in a dive and scissor the way naval aviators do in the dive, except we would endeavor to pull off sideways and back. We try to stay in a ball within a mile area, each keeping his wingman in sight.

“The leader, being the ranking man, has the first chance to shoot. The wingman, although he also wants to shoot down enemy planes, suppresses that desire until the leader has taken care of his target. Then it is the wingman’s chance, with the leader protecting him. We operate that way — just two fellows working together. It is the leader’s responsibility, however, to keep the two pairs of planes in proximity to each other.”

When asked if he goes head-on against Zeros:

“I only got two head-on passes. If the Zeros saw there was a chance of us getting around them, they’d turn and go off. We couldn’t seem to get them to tangle with us. The P-38 is a very maneuverable plane despite its size.”

Regarding new pilots, he had this to say:

“New pilots are very cocky and independent when they first arrive. For instance, a big ex-All-American football star looks at the combat pilot to whom he has been assigned for training and asks: ‘That little bird, what does he know? Am I supposed to follow that little weasel?’ Some of the most experienced pilots have ‘baby faces’ and quiet manners, which seem incompatible with their exploits.”

When asked about the P-38’s maneuverability in combat, Lanphier stated:

“We had some trouble fighting Zeros. We can’t turn and approach as fast as they can. Some of us used our flaps and slowed up, staying behind the Zeros when they turned and then turning underneath them. That was frequently effective. If we had planned an attack on bombers, I think I would have my people dive with the flaps (making an overhead approach and using the flaps to keep slow until making a run), then fold the flaps and dive. We can turn inside the Grumman with the flaps.”

Lightning Strikes

So, it was determined what plane would perform this mission, and the men who would fly them. However, distances and hurdles involved in pulling off such a daring mission were extremely daunting.

In a straight line, the range from Guadalcanal to Bougainville was 400 miles. However, there were several Japanese radar stations in the area, plus plenty of coast watchers ready to identify inbound American aircraft and sound the warning. Postwar investigation showed that several Japanese officers at Rabaul strongly advised the admiral to call off his inspection tour — fearing an American attack. Regardless, Yamamoto kept to his schedule.

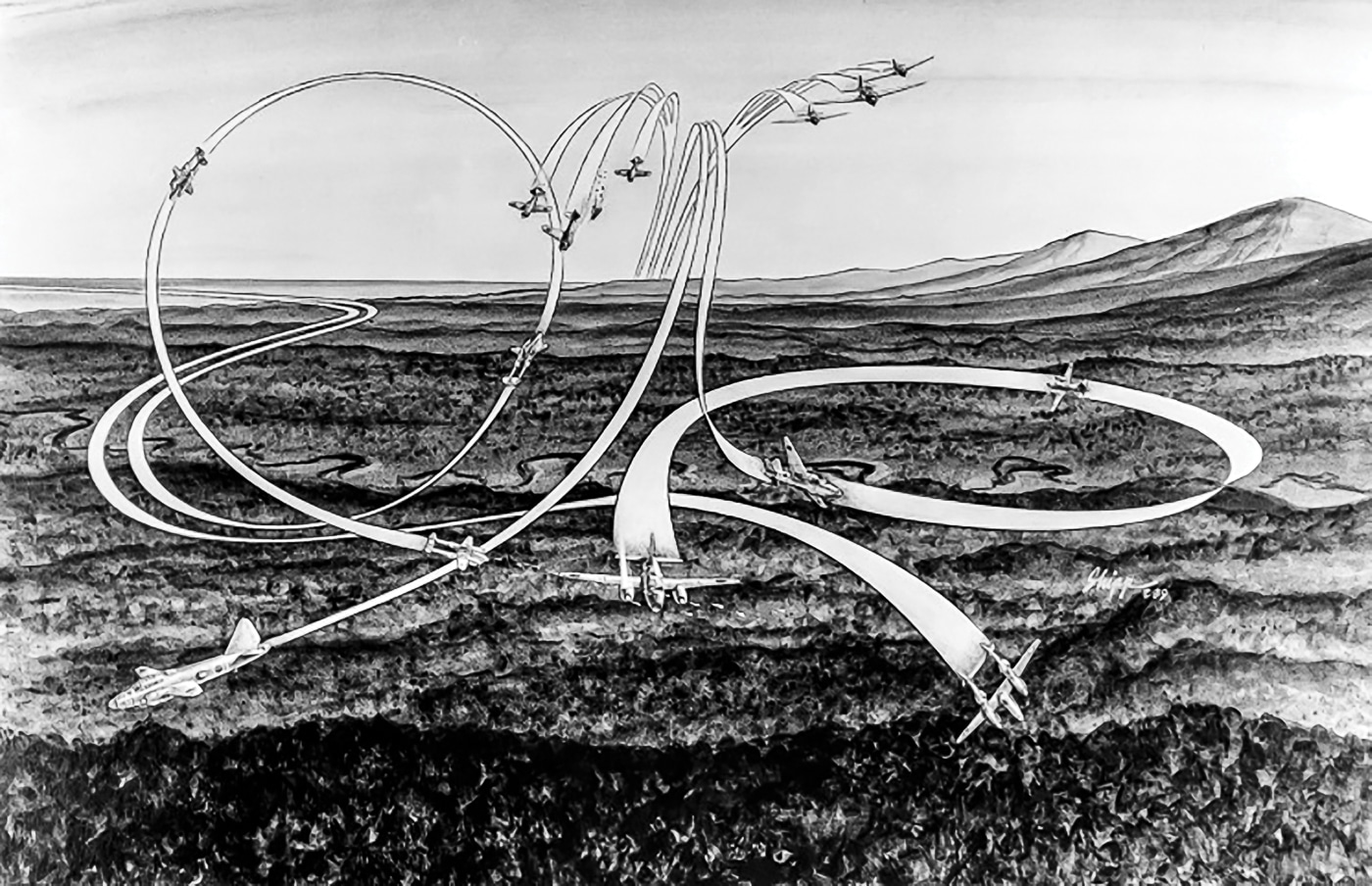

Major John Mitchell, leader of the mission, plotted an interception course that would take the 339th Squadron P-38 fighters out to sea and then back again, to emerge over Bougainville as the admiral arrived at 9:35am. The circuitous route would total 1,000 miles: 600 miles on the outward leg (at about 50 feet over the water), and 400 miles for the return flight. Extra fuel was allocated for the expected dogfights.

To make sure the P-38s had enough avgas, one of the two standard 165-gallon external fuel tanks was replaced with a 330-gallon tank. Despite the unbalanced weight in the P-38’s midsection, the fighters flew without problems.

A total of eighteen P-38s would carry out the mission, with four of them designated as the “Killer Flight”. Major Mitchell and the other 13 Lightnings would fly top cover, prepared to fight off the expected Japanese escort fighters. The plan called for the killer flight to consist of Lieutenants Thomas Lanphier, Rex T. Barber, Jim McLanahan and Joe Moore.

Troubled brewed early, as McLanahan did not make the flight with a flat tire, and Moore dropped out with a fuel line problem. Lieutenants Besby Holmes and Ray Hine moved in to take their places. After this initial complication, everything went completely to plan.

On April 18, the P-38s took off from Kukum Field at 07:25, Guadalcanal time. Major Mitchell’s dead reckoning navigation was outstanding. The Lightnings reached the interception point about a minute early (at 09:34) and immediately saw the two G4M bomber/transports descending through a light haze. The P-38s jettisoned their tanks, turning and climbing into the bombers.

Thomas Lanphier and Rex Barber turned in behind the diving G4M bombers. The four Browning .50-cal. AN/M2 machine guns and 20mm M2 cannons in the Lightnings’ central nacelles tore apart the first Betty’s right engine and sent shells crashing the length of the bomber’s fuselage. The plane suddenly flipped over and, when Barber looked over his shoulder, he saw a smoke trail that terminated in the Bougainville jungle. This Betty turned out to be Yamamoto’s plane.

At that moment, the second bomber was low over the water near Moila Point, under the guns of Besby Holmes and Ray Hine. Both pilots scored some hits on the Betty, but their speed carried them past the target. Rex Barber dove and picked up the chase, and he also scored some hits on the second bomber, which soon bellied into the water at high speed. Remarkably, Yamamoto’s Chief of Staff, Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki and two other passengers survived the violent crash and were rescued.

By this point, the Japanese escort fighters were on the scene and Rex Barber’s and Ray Hine’s P-38s received damage — but all the Lightnings exited the interception area. A Navy PBY Catalina patrol plane encountered Ray Hine on his trip home. The PBY noted his damaged P-38 (one engine feathered) and offered to pick up the pilot if he preferred to ditch. Hine asked for a compass bearing and headed towards Guadalcanal. Unfortunately, he never arrived, and no trace of his aircraft was ever found. He was the only American lost on the mission.

As for Admiral Yamamoto, a Japanese search party found his body near the crash site of the first Betty downed — thrown clear from the wreck but still in his aircraft seat, his hand on the hilt of his katana. He had been hit twice, once in the back of the shoulder and once in the head. The Japanese coroner on the scene concluded that Admiral was probably dead before the Betty hit the ground. Japanese media reported that he “met a gallant death aboard a warplane”.

The Kill Controversy

When Thomas Lanphier returned to Guadalcanal, he announced over a clear-channel radio frequency “I got Yamamoto!” as he entered the landing pattern. This was a major breach of communications security and in violation of standard procedures. Many of the other interception flight pilots reported that they heard him make the claim over an open line.

It was Lanphier who wrote the Fighter Interception Report, which described his own actions in glowing terms as being involved in the shootdown. It however did make specific mention that Rex Barber was involved in shooting down a Betty bomber. While the report mentioned the downing of three of the Zeros (one claimed by Lanphier as well), Japanese records show no losses among their escort fighters — just the two G4M bombers downed.

Kill claims have been frequently disputed since the beginning of air-to-air combat. The Yamamoto interception has been reviewed in detail several times since the war, and most of the evidence points to Rex Barber as the pilot who was responsible for taking down Yamamoto. All the pilots in the killer flight received the Navy Cross.

Thomas Lanphier was a skilled and experienced combat pilot, and whether he actually did or simply believed he shot down Yamamoto makes no difference in the final equation. The architect of the Pearl Harbor surprise attack, the day that would live in infamy, was dead. Operation Vengeance was a success.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here