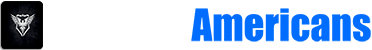

Some short-timer due to rotate off the hill came by our bunker to gloat. He wouldn’t be around for Christmas, which he informed us was tomorrow. News to me. In my view, counting days was akin to tempting fate. Life at Con Thien was dicey enough without that kind of distraction.

My bunker buddy Sergeant Steve Berntson stuck his head through the muddy culvert section that provided access to our small bunker somewhere along the hill’s cramped perimeter and squinted up at the sky. As usual, rain-swollen clouds were rolling toward us from the direction of North Vietnam, which was just three klicks north, or as we liked to say too damn close.

“Don’t guess we’ll be getting a white Christmas.” Berntson was masterful in his grasp of the obvious. “In fact, if those clouds hover like they usually do…” He paused to wipe a layer of mud from his G.I. spectacles with a section of his equally muddy t-shirt. “I’d say it’s gonna be a wet Christmas.”

About that time, we heard distant booms from across the Ben Hai River that marked the DMZ separating North and South Vietnam. All along our section of Con Thien’s perimeter, Marines began to count. Depending on which NVA battery was shooting that day, we either had seven seconds or eleven seconds until the first rounds of incoming artillery landed.

It sounded like a game show where the audience counts down to the big prize drawing. We thought it would be a big hit Stateside. Something like “Hunker in the Bunker” or “Sing for Your Shrapnel.” Regular notes we sent to Hollywood written on muddy remnants of C-ration boxes were ignored, but the game went on at Con Thien.

As the count continued, Marines all over the hill’s 1,100-meter perimeter scrambled for a bunker, a wall of soggy sandbags, or an old shell crater half-filled with muddy rainwater. Just six rounds impacted that Christmas Eve 1967, down from the usual 20 or 30, which we deemed both fortunate and unusual.

Only a couple of unlucky guys, caught literally with their trousers at half-mast during a visit to one of Con Thien’s reeking crappers, had been hit. Nothing our Navy Corpsmen couldn’t handle. Nearly everyone on Con Thien had minor shrapnel wounds, and the Docs had become expert at plucking slivers out of one body part or another. Just another dreary day on a shell-pocked little knob of dirt that the Vietnamese called the Hill of Angels.

And Peace On Earth…

When all clear was sounded, Marines began to slowly, cautiously emerge from their muddy underground hovels like groundhogs sniffing the muggy air for further threats. Infused with Christmas spirit, maybe hoping there were a couple of closet Christians among the NVA artillery gunners over on the other side of the DMZ, Berntson dug out his transistor radio, extended a bent antenna and twisted the tuning knob in an effort to pick up a signal from the American Forces Vietnam Network.

Apparently there was some truth to the report that it was Christmas Eve in Vietnam, as the military network was pumping back-to-back holiday tunes. Elvis was just winding down his rendition of “Blue Christmas” when an oily-voiced G.I. disc jockey came on with the day’s top news.

The lead story prompted hoots and croupy chuckles from everyone within earshot of Berntson’s radio. A Christmas ceasefire had been declared throughout Vietnam. The National Liberation Front in a magnanimous gesture was going to halt all offensive operations in South Vietnam for an unspecified number of days in honor of Christmas.

In a reciprocal move, the allied forces in Vietnam agreed to a similar hiatus early in the following year for Vietnamese Tet festivities. Apparently, that order had not filtered down to the artillery batteries that had just dropped HE on us a few minutes earlier. “Just goes to show you,” I grumbled. “There’s always that 10 percent that don’t get the word.”

We were harmonizing along with Bing Crosby on “White Christmas” when the Company Gunny visited our section of the line and confirmed the ceasefire reports. He pointed at Berntson’s radio and growled. “Some of you sweethearts probably heard about that ceasefire horseshit.” As usual, the Gunny was candid and direct.

“Them shoe-clerks in the rear say it’s a fact, but I don’t trust them heathen commie bastards, so don’t let me catch any of you peckerheads lollygaggin’ anywhere on this hill without yer helmets and flack-jackets.” We thought that might be the end of his tirade, but there was an afterthought that restored the Christmas spirit within Fox Company, 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines at Con Thien.

The Surprise

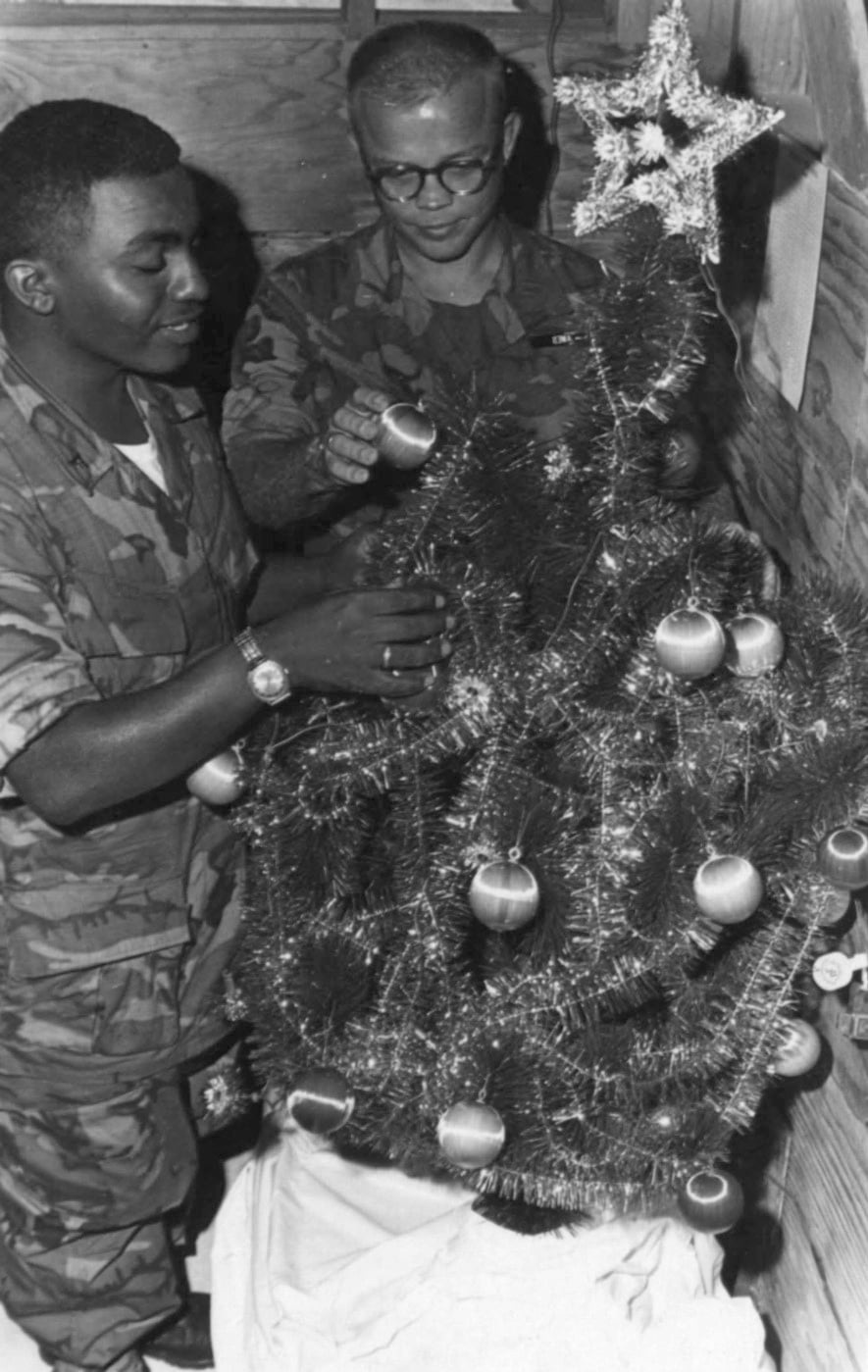

“If it don’t piss rain like it usually does … and if them air wing jarheads get off their asses …we’re gonna get a Christmas dinner tomorrow.” We were stunned. For the past two weeks, we’d been on a solid C-ration diet. We had become one with the cat-size bunker rats on Con Thien scavenging morsels of anything that looked remotely edible. Desperate battles had broken out over cookie crumbs from parental care packages.

Now they planned to bring a Christmas meal — complete with turkey and trimmings — up to us skeletal waifs? Was there something to this Hill of Angels business that we’d so loudly and roundly cursed? Speculation ran rampant throughout the bunkers. Much sleep on that Christmas Eve was lost to prayers for good weather and for a contagious epidemic of a fatal disease that would ravage the NVA gunners on the other side of the DMZ.

A major part of those prayers was answered on Christmas Day, which dawned bright and cloudless. Santa, in a gaggle of Marine Corps helicopters, had been cleared to fly. Ever cautious and leery of them heathen commie bastards, the Gunny organized us into 10-man sections.

When the chow line was set up, we would sprint down from our bunkered holding station, grab a paper plate and side-step smartly past a line of vacuum cans to receive delicacies, including roasted turkey with stuffing, mashed potatoes, gravy, and veggies topped with a big dollop of cranberry sauce. Waiting, watching and salivating, Berntson and I eyed squads of Marines delicately balancing overloaded plates and staggering back to their bunkers. It was nearly an hour before our section, the last to eat that Christmas Day, was called away to share in the feast.

The Battle Returns

We were halfway to our little hole in the ground, cradling the overloaded paper plates, when we heard the dreaded booms. I counted just four, likely the anti-christ battery, declaring that Hanoi ain’t the boss of them. Regardless, we were within safe distance of our bunker if we sprinted. But sprinting risked spilling the glorious feast on our paper plates. We hunched our shoulders over the chow and did a version of the green-apple quickstep. Berntson made it. I did not.

Focused on not spilling an iota of the food that was balanced on my rapidly deteriorating paper plate, I stepped into a waterlogged shell hole and went down hard. Four HE rounds hit well away from me as I watched my Christmas dinner disappear into the slime. Who knew cranberries would float? The last thing I remembered was Berntson pulling me up out of the mire and watching a big turkey leg floating away, chased by a flotilla of rats.

The True Spirit…

That’s when I became familiar with the true spirit of Christmas. Berntson divided his dinner into precisely equal proportions and gave me half. Basking in the glow of full stomachs, he even rescued what was left of that floating turkey leg which we washed with canteen water and enjoyed as dessert.

Every year around this time of year, I find myself remembering that time with a smile. And I’ll never again gnaw on a turkey leg without thinking about Christmas on the hill at Con Thien in 1967.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Read the full article here