Two of my favorite cartridges, .270 Winchester and .300 Holland & Holland Magnum, have just celebrated their centennial birthday.

Maintaining popularity for more than a century is quite the accomplishment in the cartridge world. For every one of the “classics” that have made that mark, there are several that fell out of vogue, and many others that have disappeared altogether.

Sure, the .30-06 Springfield, .45-70 Government, .45 ACP, 9mm Luger, .22 Long Rifle and .30-30 Winchester have all made that mark, but the .30-40 Krag, .38-55 Winchester, .300 Savage and .22 Short have lost much of their following of late. And while much of the cartridge market seems to be a popularity contest, a cartridge has to have something substantial to offer to maintain any sort of popularity for more than a century … especially considering the recent advancements in powder and bullet technologies.

Celebrating their 100th trip around the sun this year are two classic cartridges: the .270 Winchester and the .300 Holland & Holland Magnum. One is an undeniable success story that remains a highly popular choice among big game hunters, and the other has a provenance that cannot be denied, even if other cartridges have pushed it out of the limelight.

.270 Winchester

Starting with the more popular of the two—Winchester’s famous .270—you’ll find the most popular of the offspring of the .30-06 Springfield. Or, since we are delving into the history of the birthday cartridges, we might more properly say the offspring of the .30-03 Springfield, which came a bit earlier and has a case length just a bit longer than its much more popular sibling.

The .270 Winchester retains the .30-03 Springfield’s 2.54-inch case length, and the 17½-degree shoulder to handle the headspacing. It has the 0.473-inch case head diameter, which was carried over from the Mauser cartridges and fits perfectly in any long-action receiver.

Exactly where the .277-inch bore diameter came from is, sadly, lost to history. Some say it was an attempt to bridge the gap between the 6.5mm and 7mm bores, without using a metric denomination; others feel it might have been adopted from the groove diameter of the 7mm/275 Rigby. But, as far as I know, there is no definitive answer. In all my research, it seems that Winchester pulled 0.277 inch out of the air, much like they did with the 0.338-inch bullets of the .33 Winchester, and as Rigby did with their now-famous 0.416-inch bore.

Nonetheless, 1925 saw the release of the new Winchester Model 54 bolt-action rifle, chambered for the newfangled .270 Winchester. While it certainly possessed the velocity that would become so popular over the coming decades, rifle optics weren’t in vogue in that era, and the Model 54 was designed and stocked for iron sights.

Offering an enhanced velocity level in comparison to the majority of the most popular cartridges in 1925, the .270 Winchester offered bullet weights between 100 grains—a sound choice for the larger furbearers and all varmints—and 150 grains, which was considered suitable for an all-around big-game bullet. The 130-grain bullets performed wonderfully on whitetail deer, wild sheep, pronghorn antelope and black bear, while those 140- and 150-grain slugs were employed against moose, elk and other large game.

The .270 Win. Got Jacked

One would think that the flexibility and popularity of the .30-06 Springfield might have killed the .270 Winchester before it even got out of the gate, as the 150-grain ammo was stellar on lighter big- game species, and those massive 220-grain round-nose bullets would neatly handle even the heavyweight coastal bears of Alaska. But Professor Jack O’Connor embraced the fledgling cartridge, taking in from the deserts of Arizona and Mexico to the wilds of Canada, and most places in between. His writings in Outdoor Life—in an era where the opinion of a gun writer carried more weight than it seems to today—propelled Winchester’s cartridge into the annals of history, and O’Connor seemed to guarantee the future success of the cartridge.

Making good use of the original 130-grain load—with a muzzle velocity of 3,160 fps—O’Connor waxed poetically about the cartridge, ushering in the era of speed, in complete opposition to the heavy-and-slow mentality of the era. Readers followed suit, and it turned out that the .270 Winchester made one helluva whitetail cartridge. The rest is essentially history, because the generation of O’Connor readers took the torch and ran with it. Because it was so popular, it was readily available, and because it was readily available, it remained highly popular.

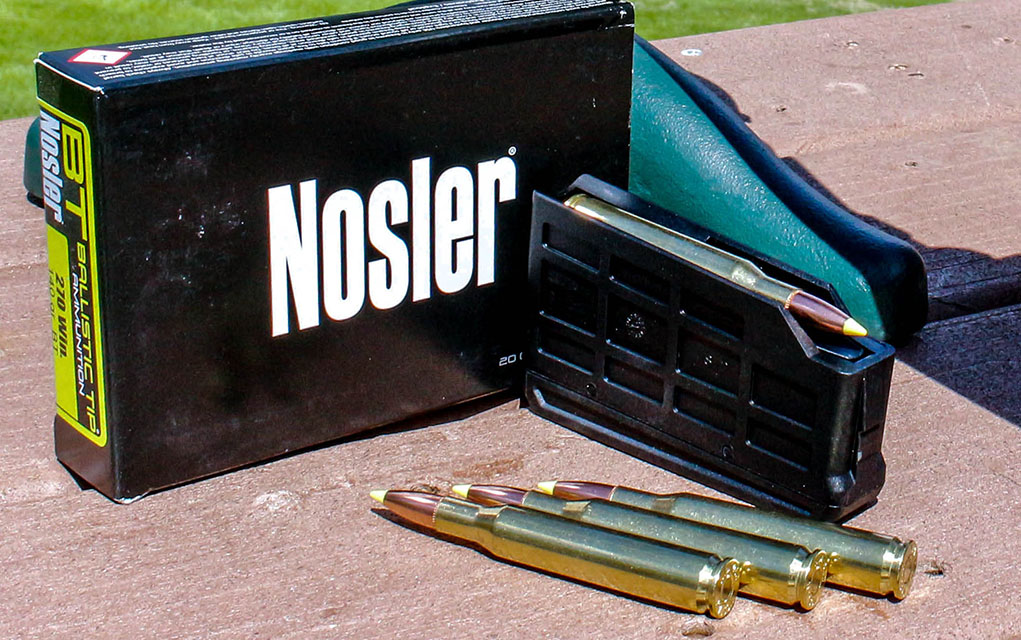

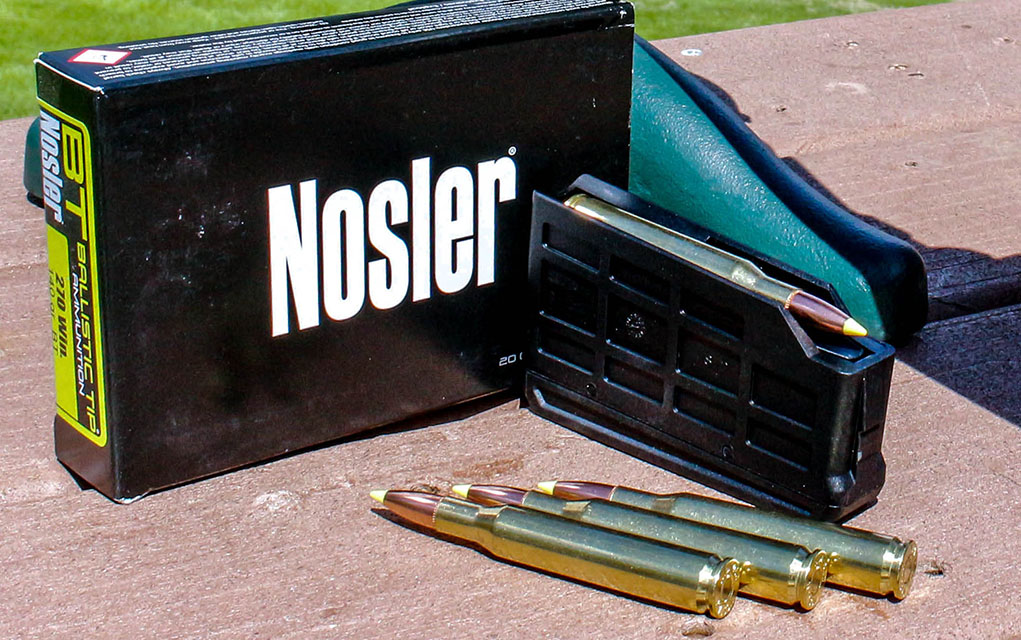

Truth is, the cartridge is a sound balance of velocity, striking energy and manageable recoil. The .270 Winchester has the attributes desirable for both Eastern deer hunters and Western hunters after mule deer, pronghorn and, yes, despite so many arguments, bull elk. As the cartridge aged, bullet technology only improved the capabilities of the cartridge, and today—in spite of the developments in cartridge, bullet, and optic technology—it still works just fine.

Despite a couple attempts at dethroning the king— namely in the .270 Weatherby Magnum and .270 Winchester Short Magnum—the only real threat to the .270 Winchester is the 6.8 Western, which employs a faster twist rate to utilize bullets heavier than those normally associated with the .277-inch bore.

And, although I’m a big fan of new cartridges, I don’t think the .270 Winchester will ever be unseated.

.300 H&H Magnum

Crossing the “pond,” the prestigious London firm of Holland & Holland announced the arrival of the .300 Holland & Holland Belted Magnum—the Super 30—in 1925. The fourth in the H&H line of belted cases—following the .375 Velopex, the .375 H&H Belted Magnum and the .275 H&H Belted Magnum—it mated the successful .375 H&H Magnum case with the .30-caliber bullets of the .30-40 Krag and .30-06 Springfield.

The first commercially successful .300 Magnum, H&H’s cartridge used the 2.85-inch case and 3.60-inch overall length of the .375 H&H Magnum, best housed in a magnum-length receiver. Factory ammunition saw a 180-grain bullet sent at a muzzle velocity of right around 2,700 fps—seemingly loaded down to the level of the .30-06 Springfield in anticipation of the effects of the heat of the tropics on Cordite—but handloaders could easily beat that figure.

The .300 H&H, like the .375 H&H, was picked up by Winchester, Western, Peters and other ammunition companies, with Winchester and Remington offering American-made rifles. In fact, in 1936 Winchester offered the .300 H&H Magnum in the initial release of the Model 70, and Remington’s 722 was embraced by many hunters as well. Ben Comfort used the cartridge to win the Wimbledon Cup—the Camp Perry 1,000-yard shooting competition—with a custom Griffin & Howe Remington 30-S rifle, proving the capabilities of the belted beast.

In the hunting fields, many successful reports drew attention to the magnum—whether or not that was a placebo effect—and the three initial loads featuring 150-, 180- and 220-grain bullets covered nearly all the bases in the big-game world, save the true heavyweights. As powder technology improved, the .300 H&H just got better, with ammunition seeing the 180-grain slugs pushed to a muzzle velocity between 2,850 fps and 2,950 fps in modern ammo. The slight 8½-degree shoulder allows the cartridge to feed ever so smoothly, while the belt of brass just north of the extractor groove handles the headspacing duties.

For those who might be recoil sensitive, yet are interested in magnum-level performance, the .300 H&H makes a fantastic choice for a hunting cartridge. I have found that, among the myriad choices of .300 magnums, the ,300 H&H is among the easiest on the shoulder, yet offers solid field performance. Yes, John Nosler was carrying this cartridge when the 1940s bullet technology let him down hard on a Canadian bull moose, but modern bullets have done nothing but help the century-old cartridge. I have taken the .300 H&H Magnum across the pond on a couple of safaris, not to mention hunting here in the United States; it has been good to me in a number of different scenarios. From whitetail deer in my native New York, to Hartmann’s mountain zebra, red hartebeest and eland in Africa, the cartridge has yet to let me down.

I’ve had a couple of rifles chambered for the excellent cartridge, including a 1959-vintage Colt Coltsman bolt gun, which my wife used to take a great blue wildebeest bull, and my current love, a mid-1980s Winchester 70 push-feed with one of the most beautiful pieces of flamed walnut I’ve ever encountered in a factory stock. The latter rifle prefers bullets with lots of bearing surface and will put three Nosler AccuBond 200-grain bullets into ¾-inch groups all the livelong day.

The Athletic Younger Brother

Marketing being a funny thing, Winchester’s own .300 Magnum is what pushed the H&H design out of the limelight. The shorter case of the .300 Winchester Magnum allowed it to be housed in a budget-friendly long-action receiver, while the ballistics of the younger case actually bettered those of the .300 H&H.

In spite of the large number of modern .300 magnums that have come to light in the past quarter century, the .300 H&H Magnum still has that “cool” factor; whenever I pull mine out at a range session or on a hunt, guys look on wide-eyed. I’ve had more than one African Professional Hunter ask to shoot my rifle or beg a cartridge for their collection. Does it make financial sense, being a rarity these days? Probably not, but there are no flies on the ballistic formula, and I will happily attest to the fact that no animal has ever been able to determine whether I was carrying a .300 H&H or a .300 Winchester.

The slight shoulder, the long, tapered case and the history that comes attached to Holland’s little gem all combine to offer an undeniable classic rifle experience, harkening back to an era when “300 Magnum” was inscribed on the barrel, and shooters knew it was a .300 H&H Magnum, as there was no commercial offering before 1963.

Whether loaded with modern polymer-tipped boat-tails or a good old round-nosed thumper of a bullet, the .300 H&H is equally at home in the woods of the East in pursuit of whitetails or black bear, as it is on an elk hunt in the Rockies, or in a leopard blind in the Zimbabwean lowveld.

With modern factory ammunition choices being limited, handloading is assuredly the way to keep your .300 H&H properly fed. It seems to be a forgiving cartridge, as you can use a good number of common propellants, and the choices of component bullets are nearly limitless. Grab a good set of dies and source enough brass to keep yourself in business, and you can hunt the rest of your days with a .300 H&H Magnum. I like a 180- or 200-grain bullet for most applications, though the .300 H&H Magnum will handle the 150-grain bullets very well, unlike many other .300 magnum cases.

Time Marches On

So, with all the progress we’ve made over the last century in case, powder and bullet technology, why in the world would a new hunter even consider one of these centennial cartridges? Well, both possess the attributes that any hunter would appreciate, giving a blend of usable features, and both have the pedigree to create that inexorable tie to the past that hunters crave so much.

And, frankly, both of these work—at normal hunting ranges—just as well as anything that has come along in the century since they were introduced. Neither was designed for dedicated target cartridge, though both have the capability to deliver fine accuracy.

Happy 100th birthday to the .270 Winchester and .300 H&H Magnum … and to many happy returns.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the July 2025 issue of Gun Digest the Magazine.

More On Rifle Ammo:

Read the full article here