In 2024, news of a prominent climber, Charlie Barrett, getting arrested for rape rocked the climbing community. Many were aghast at how this could’ve happened. Annette McGivney’s Outside article that chronicled his crimes was even titled “How Did This Climber Get Away with So Much For So Long?”

Long after the beginning of MeToo, climbing was beginning to reckon with how its communities, members, and organizations harbored and even enabled rapists, child sex abusers, and other perpetrators of sexual violence.

In all of these worthwhile discussions, one subject remained in the shadows: domestic abuse and intimate partner violence. What happens when your abuser is both your romantic partner and your belay partner?

In the sport of climbing, where partnerships and mentors are so integral to success across disciplines, how does the community respond when those partnerships turn from a source of support to a source of violence?

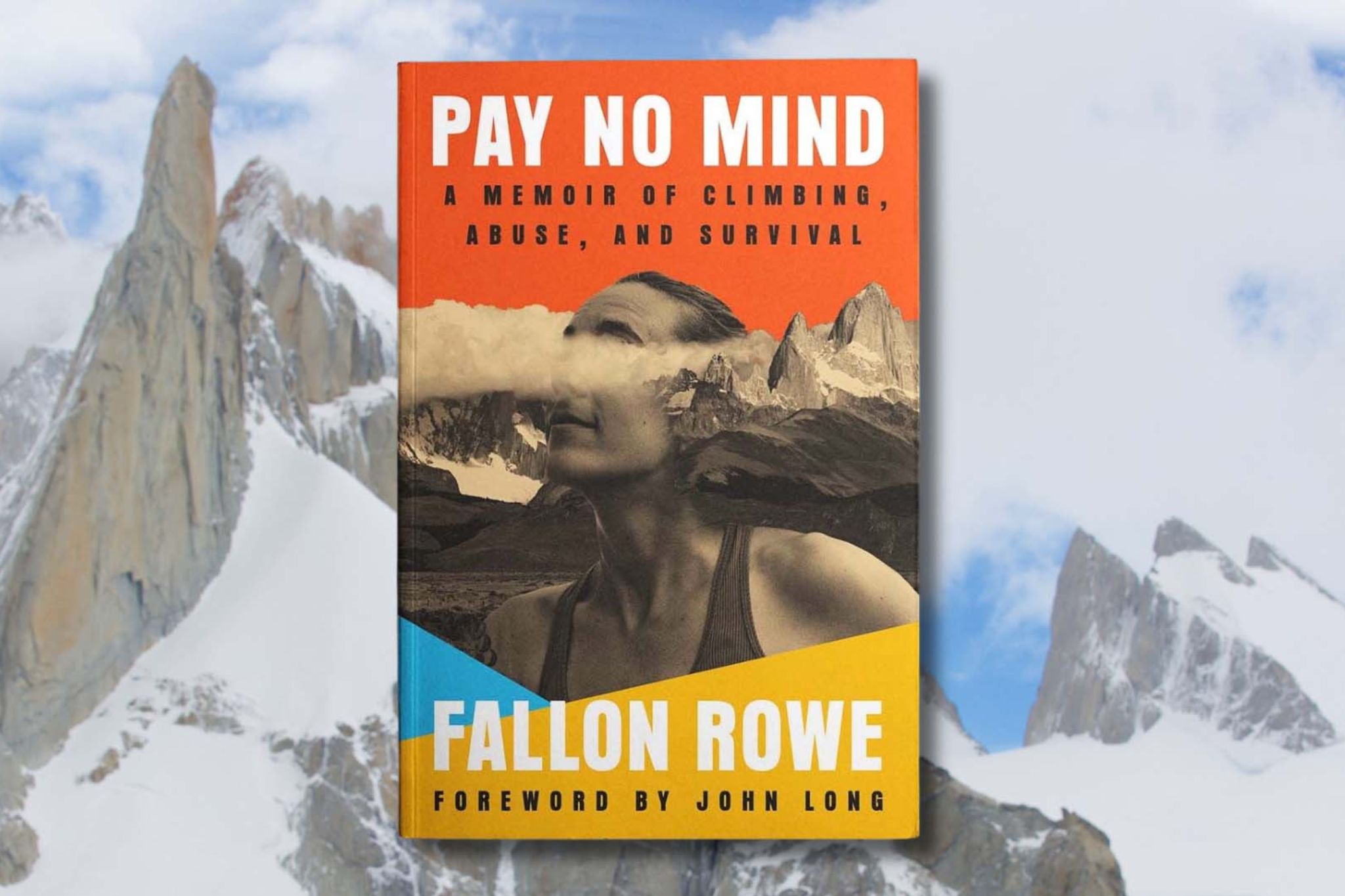

Fallon Rowe’s new memoir, Pay No Mind, pulls at this thread, retelling the 7 months she was in an abusive relationship with her boyfriend and climbing partner. In unflinching detail, Rowe recounts the series of events that led to violence, rape, and, eventually, freedom.

How could this have happened for so long?

It’s stories from survivors like Rowe that will help us grasp the full complexity of intimate partner violence, and what we as a community and as individuals can do to aid victims and prevent abuse. I read an advance copy of the book, and spoke with Rowe about her intentions and writing process.

How the Story Unfolds

Rowe’s book plays out in four parts. First, it’s her life as a young 19-year-old college student and climber in Utah. She’s overwhelmed by responsibilities, but bright and passionate and full of potential. Next, Rowe meets the charismatic Dan, and gets swept up in the joy of climbing and a new relationship. Red flags begin to emerge about Dan, but they’re easily swept aside.

Next, the duo takes a trip to climb Fitz Roy in Patagonia, and here, Dan’s all-encompassing pattern of abuse goes on full display. Trapped with no money and no escape, Rowe struggles to survive the trip and the relationship.

Once they return to Utah, Rowe continually attempts, and subsequently fails, to leave Dan, until one night, she finally breaks free.

Many memoirs about a challenge or a struggle fall into a pattern: one part before, one part during, and one part after. Rowe purposefully eschewed this structure. Readers don’t get an “after”: There are only seven pages describing what Rowe’s life looked like once she left Dan. She doesn’t detail going to therapy or processing her PTSD, and there’s a reason.

“To tackle what happened afterwards, I’d need a whole other book. I didn’t want to rush or simplify and shove it into one final part,” Rowe said. She wanted the focus to remain solely on her 7 months with Dan and what abuse looks like.

“I hope that it leaves an impression on people, especially people who’ve never been through this, or don’t have anyone in their life who’s been through something like this. I hope it helps them see it more clearly, so they can have more compassion.”

The Cycle of Abuse

While of course, by definition, a story about abuse is difficult to read, Rowe’s is particularly challenging to read, even as it’s engrossing. In Patagonia, after enduring threats and violence and verbal abuse, Rowe manages to sneak away from Dan to a hostel, and plans to take a bus back to the airport. After reading Dan belittle and attack Rowe for hundreds of pages, I exhaled a sigh of relief: She’s finally going to be free.

On the next page, my heart sunk. Dan manages to find her and steals her passport, and Rowe has no choice but to go with him.

Some variant of this happens time and time again in the book. Over and over, Rowe gets so close to leaving Dan, only to be drawn back. Rowe recognizes this cycle is hard to read, and it’s even harder to live.

Whatever frustration the reader feels with the situation can only force them to consider the frustration and desperation Rowe must have felt at the time.

“If you felt exhausted and frustrated reading this book, know you’re in good company. That was the point,” Rowe wrote in the afterword.

“I want readers to understands what it feels like to get spun round and round in an endless cycle, each phase faithfully following the last: tension building, violent episode, reconciliation. Rinse and repeat. Familiarize yourself with one of the many diagrams of it, and avoid it at all costs.”

One of the biggest misconceptions people have about abuse, Rowe says, is saying victims should just leave at the first signs of trouble. The control an abuser exerts can be complex and all-encompassing.

“I really wanted this book to show the push and pull, and wanting to leave, but not being able to leave feeling so stuck,” she said.

Supporting Victims

Most people would like to think that if they saw a person in a dangerous relationship, they’d intervene to help. And yet, Pay No Mind demonstrates both how easy inaction is and how manipulative abusers can be.

On one of their many hikes up to base camp to drop off gear in Patagonia, Dan violently swings his ice axe around as he verbally berates Rowe.

“Eventually he saw people coming down the trail, and it was like a switch was flipped — immediately, a calm washed over him. He looked completely normal, and the ice axe lazily swung by his side. I wiped my tears, incredulous at how easily he could just turn it on and off,” Rowe wrote.

“The hikers passed us without thinking anything of it. I secretly hoped one of them noticed what was happening. As soon as they were out of sight, Dan’s rampage resumed.”

This is just one episode where Rowe silently pleads with strangers, begging for someone to intervene and come to her aid. She chose the title, Pay No Mind, to reflect these moments.

“When we pay no mind to something, we’re almost willfully ignoring it. And I wanted that as the title because there were people who knew what was going on, or saw punches or certain things happen, and they didn’t step in,” Rowe said.

“It takes all of us as a community to try to warn each other about these kinds of people or speak up at the crag if you can.”

Rowe understands the challenge this kind of situation presents. Abusers can be master manipulators, and directly confronting one can be dangerous or make things worse for the victim. She emphasizes that any action you take should protect the victim; having a conversation alone with them and offering support is an important first step.

Climbing Culture

While abuse can happen to anyone in any situation, or in any sport, the unique qualities of climbing can create environments that act as a breeding ground for unhealthy relationship dynamics.

When Rowe met Dan, he promised he’d make her a stellar crack climber, he’d take her across the world, and she’d get to the next level if she was with him.

“This kind of power dynamic is really common, especially in climbing, because you need a mentor, and they’re often a man, and they’re often older than you, and that inherently creates this power dynamic and imbalance, and it can put you in a position, if you’re really driven, like I was, that you’ll put up with a lot to keep moving towards your dreams,” Rowe said.

“And I don’t want other women or girls to think that they have to do that, and for them to know that there are other options.”

“Pay No Mind” is available for preorder here before its November 26, 2025, release. You can hear more from Fallon Rowe on her Instagram.

Read the full article here